I had the opportunity to hear Jason Fried, the founder of the project management tool Basecamp, speak this spring at Northwestern University’s Kellogg Business School Entrepreneurship Week. Jason said a number of interesting things based on his book “Rework”, but the most memorable part of his speech were his comments on “paying for services”. I found this fascinating for two reasons: (1) Jason made it clear that when you charge for services you are held to a standard of quality and are forced to deliver a great product, especially if you have a peer utilizing a “freemium” model (giving basic services for free to subsequently sell a premium service or monetize off the user data). And (2) how it was almost identical to Raju Bhai and Saath’s philosophy of having the urban poor pay for services. At Saath, we believe that if you give a service for free, the recipient is (1) left with no stake in the quality and (2) is not motivated to consume the service. For example, let’s say someone gave you free food and it tasted terrible. If you complain, the person who gave it to you will say “how can you complain, it’s free”. Similarly, if I offer free English classes on Saturdays, no one will show up – why would anyone want to study on the weekend? But if someone is charged for it, , they will show up every Saturday to maximize the money they invested in the services. Market-based development at its best.

India Abroad.

•December 3, 2010 • Leave a CommentI’ve been back in the States for 18 months and while I’ve gained 15 pounds, been ridiculed for my mustache/beard (I caved and shaved), and lost my mediocre Gujarati skills, India has still been a very key part of my life. I have continued to work closely with Rajubhai, Keren and Bijal (09-10 Fellow) at Saath and spent November in India to work closely with our new social enterprise incubator called R3. I am going to add a few more posts to ‘findingrickshaw’ and then will be moving to a new blog: http://www.rickdesai.com where I’ll continue to blog about development in India and R3’s new program, but also about my new venture.

My Name is Khan.

•October 17, 2010 • Leave a CommentI love Bollywood for its business model, but am not the the biggest fan of its movies. While they are (usually) entertaining, their success is measured on box office records not on cinematographic quality. My Name Is Khan was different. It touched on an Indian-Muslim American’s plight after 9/11. Bollywood Hero Shahrukh Khan played the character of Indian-born Muslim man born with Aspergers ssyndromde. He moves to America in his twenties, where ideally, he would be afforded religious/cultural freedom. However, he is discriminated universally: by his Muslim family for dating Amiercan-born Hindus; from Hindu-American Indians for being Muslim, from non-South Asian Americans for being Muslim, and the US Govt for being a terrorist. There was some Bollywood fluff and flair, but the message was almost Crash-esque, forcing viewers to challenge and question disabling stereotypes.

Readers and Visitors.

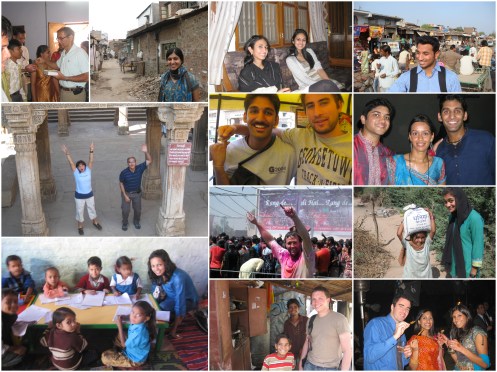

•July 12, 2009 • Leave a CommentOne of the best parts of the past 10 months was sharing with close family and friends from home. Whether they came to visit their family, shop for weddings, travel India or to see me, it was great to give the “rick slum tour”, share Saath’s development work and just talk about America over nice dinners. Their perspectives were refreshing and I enjoyed discussing (and arguing) my new revelations about India and development.

Similarly, this blog has given me a forum to share the good, bad, beautiful and sweaty of India with friends, acquaintances and strangers. Prior to this, I felt uncomfortable putting my thoughts on paper. Surprisingly, I’ve found it both therapeutic and fun to blog, share and emote. And while I know half of my page views were from my dad (he also visited me twice), I hope that you learned something new about India and enjoyed the blog as much as I did.

I look forward to continuing it when my path crosses India’s in the future.

Thanks for visiting and thanks for reading.

“Mummy Ni Yadh Che?

•June 29, 2009 • Leave a CommentThis year marked the 23rd anniversary of the death of my first mom, Rita. While I didn’t get to connect with her distant family and friends in Mumbai, I did get to hear about how she lived. Whether voluntarily or prompted, my dad’s family shared many stories with me. They said that they can’t believe my dad got so lucky in marriage…twice. They told me how she preached independence to all of the younger women encouraging them to “travel and see the world”. They were in shock when my mom had no qualms in asking my dad to do household chores and baby tasks – it was the first time they saw a man changing diapers. They said her Mumbai-American Gujarati was apparently hilarious (I wonder what they think of mine…). I heard how when she saw my dad’s sister’s home she found it unacceptable and, together, they bought her a new house. And they told me about her beauty and grace, how Priti and I have her eyes, and how when Priti’s hair is curly, she looks just like her.

When I asked “mara pela mummy ne yadh che? (do you remember my first mom?)”, I always heard the same response:

“How could we ever forget her? No one could.”

My Gujarati Family.

•June 29, 2009 • Leave a CommentWhen given the option of working in Ahmedabad, I almost chose against it. I thought that living near family would inhibit my freedom to learn, work and live on my own in a foreign and challenging environment. It would have been a huge mistake.

My dad still has a large family base in Ahmedabad and Gujarat. My dad’s older brother, Kirit, is our family protector. Even with modest means and at the age of 65+, he looks after all our family in India and all of our American relatives interests here with great care and without hesitation. He is methodical, incredibly patient, thoughtful and extremely loyal and kind. My dad speaks so highly of him and with so much love, and now I know why. His grandkids, Harsh (15 running) and Kanisha (9 completed)), are my best friends here. They taught me Gujarati and translated Hindi movies for me. Harsh’s curiosity and love for history is refreshing. Kanisha has a way with words and a flair that is constantly entertaining. I’ve begged their mom, Bhargavi, to let them come to the States with me. Unfortunately, she is too good of a mom, as the kids keep saying “we won’t go anywhere without her”. She has answers to all my questions and we’ve had great conversations about family and life in general. Getting to to be part of Kirit Kaka, Sushila Kaki, Parag Bhai, Bhargavi Bhabi, Harsh and Kanisha’s family rather than just a 2-week guest from America, has been without question the best part of my experience in India. I’ll forever be indebted to them.

On the same note, I also spent time with my other relatives in India. My dad’s older sister, some cousins and cousins’ kids (who are older than me?!), my dad’s cousins, etc. I saw some of Smita’s family in Baroda when she came to India. It’s incredible how much proximity affects your relationships. I felt sad that I had all this family in India who I’ve met before on short visits but never really “knew”. But I guess the best part about family is that you can alway (re)connect through the familial bond. Without the multitude of dinners I ate at relatives houses’, I would have lost at least another 10 pounds.

Ramesh Kaka, my dad’s older cousin, his brother Satish Kaka and their families are the perfect example. We always visited them when we came to India, but other than name and appearance I couldn’t tell you much about my uncle, aunt or my cousins and their families. They fed me, blackberried me, and even came to work with me. After spending time I can tell you that it’s families like Ramesh Kaka’s that gives you hope to India’s future. They treat everyone – family, employees, domestic help, friends – with dignity and respect. It’s a far cry from how you see people generally treat others here, especially minorities and those of “lower caste”.

It was amazing to see a new side of Ahmedabad, my family; and to share with them the incredible work that Saath does here.

Thank you, Saath.

•June 26, 2009 • 1 CommentThis past Friday was my last day at Saath. Natassia and I found it difficult to leave. We visited the field staff one last time. Rajubhai took us to dinner. We bough everyone ice cream. They bought us lunch. We made a collage. And they gave us presents. I am extremely thankful to have been placed at such an incredible organization with such motivated people, work with Natassia and learn from Rajubhai.

Not sure how well I can articulate what I learned, but the below is my attempt:

1) Community Ownership. Almost all of Saath’s programs require a monetary contribution from the community. As Divyang, the MFI program manager explained, “Let’s say you are eating free food that tastes awful. You can’t complain because you didn’t pay for it”. Paying for services promotes community ownership and accountability from service providers. An invaluable result of this is that the community leadership has blurred with Saath’s program staff. The community has a say in every programming decision and in most cases is the direct implementing agent. This has achieved much more than empowerment – it has led to the community managing its own development.

2) Recognition Model. I first heard it in training and then observed it through Rajendra Joshi, the founder of Saath: “You can achieve anything as long as you don’t care about who gets the credit.” Saath has embodied this from the top-down. They are happy to give credit to partners – private sector or government or community. As a result, these partners are more likely to support Saath in the future.

3) People Professionally.

Saath Staff. I am amazed by the talent and humility of Saath’s management. With architecture, financial, social, zoology backgrounds, each brings an abundance of skill to their work. Mixing this with their passion for the organization’s mission makes Saath an incredible organization.

Community-Based Organizations. Similarly, Saath’s CBOs are just as impressive. You can’t spend five minutes with Yaqoobbhai, Madhuben, or Devuben without touching their feet out of respect or asking for their guidance.

4) People Casually. It was a pleasure walking into the office every morning. From Hemali’s hellos to Shomnaben’s delicious tea, the office environment was a perfect balance of friendly, venture, productive and fun. Everyone was very willing to help explain anything and everything. Most importantly, though, I learned about humility and respect. While I’ll always be impressed with the work and reach of Saath, I’m more appreciative of how no one takes themselves too seriously and everyone is treated equally. I am grateful to have worked and learned from people with such great commitment, diligence and intellect. And I’ll always remember how much fun coming to work at Saath was.

Madhuben and Microfinance.

•June 24, 2009 • Leave a CommentOne year ago, I thought I understood microfinance. I had done my research, read Yunnis’ book, and loved Kiva. I thought the premise was simple: provide the poor access to loans, allow them to invest in small enterprises and help them escape from poverty. Since then, I’ve worked with these borrowers, heard Yunnis speak, and debated the merits and ethics of lending to the poor. I now know that microfinance isn’t an immediate and magical solution to poverty reduction. Rather, it is a gradual, (can be) responsible and generational way for the poor to participate in their own development. Much of what I learned was through Saath’s microfinance program, the success of which can be largely attributed to Madhuben

—

She dresses in traditional saris, prefers to speak only in Gujarati, and claims to have never fulfilled her dream of becoming a teacher. A modest description of someone who manages 10,000 banking clients. Hearing her speak about default rates and collateral rates is akin to listening to a CFO during an earnings call. She is Madhuben and she is Saath’s community microfinance coordinator. Madhuben grew up with microfinance, a decade before Yunnis won the Nobel peace prize and Kiva became a global buzzword.

Joining Saath in 1992, Madhuben was one of the few women in her community to have made it through the 12th standard. She earned Rs. 250 a month teaching for Saath’s Balghars program, a much needed slum pre-school program. Over the next four years, Saath’s presence and community staff of primarily women grew. However, they nor their work were readily accepted in the communities. They were assumed to have little qualifications and were often told that “as women, they aren’t capable of working”. To address the lack of services to and power of women, Madhuben and a few others formed a discussion group of weavers, sewers and teachers. News spread virally and soon, 100 members had joined.

They quickly realized that the most pressing issue was the inability to safely save their earnings for various reasons, including their husbands gambling and drinking their savings. They began collecting Rs. 25 a month and depositing the aggregated savings into interest-earning bank accounts. Their reach accelerated. In two years, they covered almost 1,500 households in the Praveen Guptanagar (PG1) slum area. Madhuben managed 200 of these households. The women gained a dependable place to save and earn interest and Madhuben and her team became respected community leaders. The latter proved invaluable. Many of the amenities and services present in PG1 today such as toilets, street lights, and electricity, were conceived by Saath and the government but were implemented by Madhuben and other local leaders. The mistrust often associated with NGOs and government schemes was mitigated as this group effectively conveyed the program message.

In 1999, as the quantum of savings accumulated, Madhuben and her peers realized that they should also lend money. Microfinance is often marketed as “providing the poor access to lending”, but in reality, the poor have always utilized credit. Long before private equity and venture capital firms realized the market at the bottom of they pyramid, local private money lenders were lending to the poor. These lenders were keenly aware that they were the only source of funds and thereby could lend at a discount and charge 5-10% interest rate on the principal per month. For example, a borrower would receive $90 on a $100 loan and be required to pay $10 each month in interest (10% of $100 regardless of whether the loan was paid back on day 2 or day 360). The resulting 120%+ interest forced borrowers into a unresolvable cycle of debt.

Madhuben says the solution was obvious: “Use the savings to fund loans with responsible terms and rates.” Today, they offer a 24% interest rate charged to the current balance, not the principal (which works out to ~12.5% per annum). Each percent is perfectly allocated between mandatory savings, default protection and administration fees. All profit is given is distributed to the clients as dividends. They lend to joint liability groups – teams of of 4-5 people – to mitigate individual default risk.

Today, microfinance is broadly defined as financial services to the poor but the players and offerings are vast and distinct. At the base level, groups of 10-20 women gather and contribute small savings on a weekly or monthly basis. These “Self-Help Groups” (SHG) then lend out money to the most deserving or vulnerable. On the other side of the spectrum, you have investors playing in the secondary market of microfinance. Mega-million dollar funds have been created to invest in microfinance institutions. With above market returns, these investors have the satisfaction of generating profits and commitment to the BOP development.

Here is where the debate begins though. The increased investment has led to growth of lending into new impoverished areas. Competition and scale ultimately drive down rates, which start off below private lending terms. However, the reach of these microfinance institutions is limited to lending and excludes savings and insurance, and is dependent on external capital. Conversely, institutions that depend on savings to fund loans are have slower growth and consequently, reach and impact. Aware of the ongoing discussion, Madhuben says that lending should only be one part of financial services to the poor: “Microfinance is microlending, savings and insurance. It should be a suite of products that are managed and owned by the community. Without the other products, we would become financially handicapped.”

“Twenty years ago”, she continues, “women had limited or no career options. Homes didn’t have toilets or running water. People in PG1 were perpetually in debt. Today, women are gaining rights and respect, our homes look developed and the difference in interest rates leads to more savings. It is a gradual process, but my children will have better lives. They are even saving in their piggy banks today.”

While Madhuben has benefited from microfinance, she is also why it works so well. Without people like her, microfinance is just a theory. Much of what was once just a large SHG and now is a combined portfolio of Rs. 2.5 crores of savings and loans (1 crore = 10mm) is a result of the application of her initiative, creativity, leadership and modesty.

Divyang, SAATH’s MFI program coordinator and technically Madhuben’s supervisor, admits who the boss really is, “At first glance, I underestimated her but soon I learned more about microfinance in a few days with Madhuben than I had ever known.” He wonders out loud what she would be doing in different circumstances: “In spite of not having a full education, she manages an entire financial system. She is capable of anything and could easily be leading a large company. For her, sky is the limit.”

As humble as ever, Madhuben responds, “All I ever wanted to do was teach. By teaching, I could meet more people, understand and help them achieve their dreams. I still want to be a teacher.”

I Am Me – Guest Blog.

•June 22, 2009 • Leave a CommentMy perspective of being Indian continues to expand. Growing up in America, I equated Indian with Gujaratis who lived in Michigan, ate dhar, bhat, shak, and danced with sticks near Halloween and before weddings. In highschool, India became a country of various cultures – I was told Gujaratis were cheap, Punjabis liked to drink and dance and south Indians were religious. In college, I learned that Indians were also Christian, that Pakistan and India don’t get along, that South Goa does not have nightlife and that one day, I wanted to live in India.

The Indian portion of my Indian-American identity continues to add layers (I’m a mixture of the Khadaytata and Anavil Vaishaya and Chaorta Patidar). However, the complexity of identity is much more relevant here. Every city, region, state, and geography is unique, whether natural or enforced: languages, cultures, religions, stereotypes, caste and beliefs.

The below post is from my friend, Keren. She explains her diverse and proud Indian identity.

—

I am Me

I am a mixed breed of many bloodlines, so infused that I cannot tell whether my hair comes from my maternal Spanish great grandmother or whether my eyes are English or my nose is French. What I am sure of is that I was born in Ahmedabad, India, of a Goan father, and Anglo-Indian mother (Born of a French father and Indian mother).

My ancestry is as mixed as my feelings once were, about who I am and how it makes a difference to anyone or myself where I am from. I have answered the questions of, ‘What is your nationality?’, ‘What are you exactly (caste, religion, State)?’, ‘Are you Gujarati/Parsi/Delhi-ite/Mumbai-ite etc. etc.?’ With many different responses, most of which were aimed at moving the conversation along rather than dwelling on this one aspect.

Having studied in a different State, Uttranchal (erstwhile Uttar Pradesh) for 10 years in a boarding school, with friends from all over India and the globe, my orientation was very cosmopolitan (if I say so). It never mattered where you came from, it mattered that you were one of the 300 odd girls, now confined to the life of the Central Jail of Mussoorie (C.J.M aka the Convent of Jesus and Mary, Waverley, boarding school for girls).

I grew up within a relatively safe environment, but where one had to fend for themselves, deal with the emotional hassles without going crying to mommy or daddy and take punishment like a grown up. On the other hand, we were sheltered from the crimes of the world around us, well to a larger extent than most. A sense of humour was essential to deal with the ups and downs. This sense of humour has gotten me through some pretty rough times, it allows me clarity on what is really important in life.

My family is made up of forward thinking, broad minded (to an extent), highly intelligent people who have the ability to not expect a homogenous environment. My dad ran an NGO working on issues of rural development, organic farming and sustainable development for poor and marginal farmers. I grew up observing village life, on numerous trips with my dad to the field. My parents taught me a great love for all creatures of God, people and animal alike. No one was better or worse.

I am Catholic. I was born Catholic, but my understanding of religion was never restricted to the church. I have an extended family that includes Parsis, Hindus and Sindhis. My father read books of many great teachers including Buddha and about Islam. My religion has always been based on what good I can do, rather than how many times I went to church. My relationship with my God is personal and I don’t care what the contemporary discourse is, it is based on the belief that there is something greater than all of us out there, whether we call it the universe, karma, Gaia, Yahweh, Allah, Bhagvan or any other name – it is there.

Apart from – where I come from, my family, my education and my religion, it is the personal choices that I have made, which make me who I am. I am a woman with a sense of humour and limitless hope who believes in something greater than herself, understands the enormity of every living being and attempts to comprehend the finiteness of life.

-Keren

Human Rights?

•June 21, 2009 • Leave a CommentA month ago, Ekta, my friend Nilam and I went to a port city called Mundra in western Gujarat to visit our fellow fellow Diane. There we saw the true depth of poverty in India. It was eye-opening. The work that we do at Saath ultimately focuses on the middle to top of the bottom, where people are capable to at least contribute to services. Slum residents have access to services, albeit sub-par, but access none the less. Rural migrants have at least the choice to seek new opportunities. In the fishing villages and salt panning communities that we visited, opportunity does not even exist. Even after 12 hour work days in the intense 115 heat, daily wages are not guaranteed nor is a supply of food. Things that we are trying to improve on in the slums like shelter, education, healthcare, banking, aren’t even imaginable here. Many of the people we visited said they fully expect their children to engage in the same work – not because they don’t want their kids to have a better life, but because they are confident that there are no other options. They are right. Markets and enterprises don’t work here. Every child here is born without basic human rights.

Comments.